Olivier J. Walther, University of Florida

Jennifer Sheahan, Sahel and West Africa Club Secretariat

Security challenges in West Africa are deeply intertwined with other forms of fragility, including food insecurity. Addressing these interconnected issues requires a more integrated approach, one that combines diverse data sources and analytical tools. This provides insights into the complex relationship between violence and food insecurity.

During a presentation to the Food Crisis Prevention Network (RPCA) in April 2024, we demonstrated how leveraging our Spatial Conflict Dynamics indicator (SCDi) alongside food security data provides a comprehensive view, pinpointing regions where both challenges intersect. This territorial approach enables policy makers to develop more targeted, place-based responses for areas most vulnerable to these overlapping sources of fragility.

- Fragile territories: where violence and food insecurity overlap

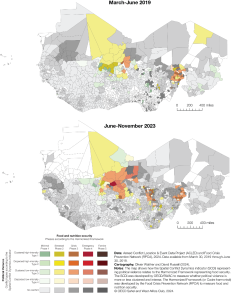

Regions plagued by repeated violence are at greatest risk of severe food insecurity. This link is clear when comparing food insecurity data with the locations of major violent events from June to November 2023. Areas such the Lake Chad, the Central Sahel, and northwest Nigeria – major centres of violence – are prime examples where conflict and food crises overlap.

Food insecurity data is sourced from the Cadre harmonisé, a tool classifying the severity levels of food insecurity using an internationally recognised scale.

- Concentrated violence mirrors acute food insecurity

By combining the Spatial Conflict Dynamics Indicator (SCDI), which measures the intensity and spatial distribution of violence, with the Cadre harmonisé food security data, we observe that acute food insecurity often coincides with areas of concentrated violence.

In June 2019, regions like Liptako Gourma and Lake Chad were severely affected by both high levels of food insecurity and violence. By 2023, and Liptako remains a critical hotspot, with the food crisis extending into eastern Burkina Faso, a country at the epicentre of armed group violence in the Central Sahel since 2019.

In 2019, Burkina Faso was shaded in yellow and light green, reflecting concentrated violence and phase 1 and 2 levels of food insecurity. By 2023, however, more areas have shifted to orange, reflecting sustained levels of concentrated violence and worsening food insecurity, reaching phase 3 levels. As shown in the maps, areas facing the most severe food insecurity are often the same places experiencing the most geographically concentrated violence. In other words, where violence is expressed in specific places and on a repeated basis, the risk of facing severe food insecurity is highest.

- Moving forward: Towards more integrated and effective responses

The overlapping fragilities of conflict and food insecurity highlight the need for integrated, place-based policy responses. These strategies must be tailored to address the specific vulnerabilities and conditions unique to each region.